On June 9, 2020, the World Trade Organization (WTO) Appellate Body circulated its reports relating to the Australia – Tobacco Plain Packaging cases. The reports issued the decision regarding the appeals brought by Honduras and the Dominican Republic against the findings of the WTO Dispute Settlement Body (DSB) panels and will likely be the last by the Appellate Body in the foreseeable future. A copy of the reports is available here.

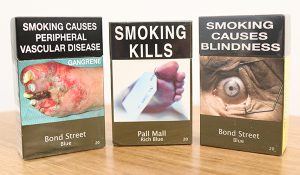

This dispute examined the TRIPS-consistency of Australian laws that regulate tobacco products by imposing restrictions to their trademarks and their packaging. These restrictions are meant to discourage smoking by making the packaging less appealing.

The Appellate Body upheld all of the panel’s findings, concluding that the regulations requiring the plain packaging of tobacco products are compatible with Australia’s WTO commitments, including those relating to trademark protection.

One key aspect of the reports circulated last week, however, dodged an important issue: the legal standing of the 2001 Doha Declaration on TRIPS and Public Health.

KEI has previously analyzed the original panel reports. An important reasoning of the original panel is provided in paragraphs 7.2407 to 7.2411 of the reports, which examined the relation between the Doha Declaration and the TRIPS Agreement. In paragraph 7.2410, the reports concluded that “[t]he terms and contents of the decision adopting the Doha Declaration express, in our view, an agreement between Members on the approach to be followed in interpreting the provisions of the TRIPS Agreement.”

7.2410. In this instance, the instrument at issue is a “declaration”, rather than a “decision”. However, the Doha Declaration was adopted by a consensus decision of WTO Members, at the highest level, on 14 November 2001 on the occasion of the Fourth Ministerial Conference of the WTO, subsequent to the adoption of the WTO Agreement, Annex 1C of which comprises the TRIPS Agreement. The terms and contents of the decision adopting the Doha Declaration express, in our view, an agreement between Members on the approach to be followed in interpreting the provisions of the TRIPS Agreement. This agreement, rather than reflecting a particular interpretation of a specific provision of the TRIPS Agreement, confirms the manner in which “each provision” of the Agreement must be interpreted, and thus “bears specifically” /fn 5011/ on the interpretation of each provision of the TRIPS Agreement.

Honduras appealed this portion of the reports (WT/DS435/23, page 2) and the Dominican Republic incorporated by reference the claims made by Honduras (WT/DS441/23, paragraph 16). Honduras argued that “the Panel err[ed] in law in its analysis by finding that paragraph 5 of the Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health constitutes a subsequent agreement under Article 31.3(a) of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties.” (WT/DS435/23, page 2) In Honduras’ view, the Doha Declaration “relates to the question of access to medicines and patents, and does not relate to any provisions of the TRIPS Agreement concerning trademarks.” (WT/DS435/AB/R, paragraph 6.656)

In their response to the appeals brought by Honduras and the Dominican Republic, Australia argued that the panel cited the Doha Declaration “to merely confirm that public health considerations are ‘unquestionably’ among the societal interests that can ‘justify’ an encumbrance upon the use of trademarks.” (Appellee Submission of Australia, paragraph 242) In the opinion of Australia, “[w]hether or not the Doha Declaration constitutes a subsequent agreement… is ultimately beside the point” because “Article 8.1 of the TRIPS Agreement by itself, makes clear that Members may adopt measures necessary for the protection of public health.” (Appellee Submission of Australia, paragraph 242)

As a third party participant in this dispute, the United States filed a submission relating to the appeals by Honduras and the Dominican Republic. The United States said that “[t]he issue of whether statements agreed by Members may constitute a ‘subsequent agreement on interpretation’ has raised difficulties for the functioning of some WTO committees.” (U.S. third participant submission, paragraph 14) The United States further said that “[r]ather than engage in this appeal on this issue, the Appellate Body could instead exercise judicial economy over Honduras’s claim of error, which has no bearing on the outcome of any appeal of the Panel’s legal interpretation or conclusion under Article 20.”

The Appellate Body addressed these arguments in paragraphs 6.656-6.659, copied below.

6.656. Finally, Honduras asserts that the Panel erred in relying on the Doha Declaration in its interpretation of Article 20. In Honduras’ view, the Doha Declaration is not relevant to the interpretation of Article 20 because “it relates to the question of access to medicines and patents, and does not relate to any provisions of the TRIPS Agreement concerning trademarks.” fn/1691 According to Honduras, “[t]he Doha Declaration is not, and was never intended to be, a more general declaration that would seek to allow Members to adopt public health related measures in violation of the TRIPS Agreement in general or of the section on trademarks in particular.” fn/1692 Australia responds that the Panel referred to the Doha Declaration to merely confirm that public health considerations are “unquestionably” among the societal interests that can “justify” an encumbrance upon the use of trademarks. fn/1693 In Australia’s view, in any event, “[w]hether or not the Doha Declaration constitutes a subsequent agreement… is ultimately beside the point” because “Article 8.1 of the TRIPS Agreement, by itself, makes clear that Members may adopt measures necessary for the protection of public health.” fn/1694

6.657. We recall that paragraph 5(a) of the Doha Declaration provides that, “[i]n applying the customary rules of interpretation of public international law, each provision of the TRIPS Agreement shall be read in the light of the object and purpose of the Agreement as expressed, in particular, in its objectives and principles.” We agree with the Panel that paragraph 5(a) of the Doha Declaration reflects “the applicable rules of interpretation, which require a treaty interpreter to take account of the context and object and purpose of the treaty being interpreted”.fn/1695 Accordingly, regardless of the legal status of the Doha Declaration, we see no error in the Panel’s reliance on this general principle of treaty interpretation.

6.658. Furthermore, we note that the Panel referred to paragraph 5(a) of the Doha Declaration to confirm that “Articles 7 and 8 of the TRIPS Agreement provide important context for the interpretation of Article 20.” fn/1696 It appears that the Panel had reached the conclusion about the contextual relevance of Articles 7 and 8 of the TRIPS Agreement before it turned to paragraph 5(a) the Doha Declaration and used the latter to simply reconfirm its view. fn/1697 In particular, before turning to the Doha Declaration, the Panel observed that “Article 8 offers … useful contextual guidance for the interpretation of the term ‘unjustifiably’ in Article 20.” fn/1698 The Panel also remarked that the societal interests referred to in Article 8 may provide a basis of the justification of measures under Article 20. fn/1699 Thus, we agree with Australia that, in any event, the reliance on the Doha Declaration was not of decisive importance for the Panel’s reasoning since the Panel had reached its conclusions about the contextual relevance of Articles 7 and 8 of the TRIPS Agreement to the interpretation of Article 20 before it turned to the Doha Declaration. The Panel relied on the Doha Declaration simply to reconfirm its previous conclusions regarding the contextual relevance of Articles 7 and 8 of the TRIPS Agreement.

6.659. In sum, the ordinary meaning of the term “unjustifiably”, as read in the context of other provisions of the TRIPS Agreement, indicates that Members enjoy a certain degree of discretion in imposing encumbrances on the use of trademarks under Article 20 of the TRIPS Agreement. fn/1700 In order to establish that the use of a trademark in the course of trade is being unjustifiably encumbered by special requirements, the complainant has to demonstrate that a policy objective pursued by a Member imposing special requirements does not sufficiently support the encumbrances that result from such special requirements. We agree with the Panel that such a demonstration could include a consideration of: (i) the nature and extent of encumbrances resulting from special requirements, taking into account the legitimate interest of the trademark owner in using its trademark in the course of trade; (ii) the reasons for the imposition of special requirements; and (iii) a demonstration of how the reasons for the imposition of special requirements support the resulting encumbrances.

fn/1691 Honduras’ appellant’s submission, para. 256.

fn/1692 Honduras’ appellant’s submission, para. 256.

fn/1693 Australia’s appellee’s submission, para. 242.

fn/1694 Australia’s appellee’s submission, para. 242.

fn/1695 Panel Report, para. 7.2411.

fn/1696 Panel Report, para. 7.2411.

fn/1697 Panel Report, paras. 7.2402-7.2406. In particular, before turning to paragraph 5(a) of the Doha Declaration, the Panel concluded that Articles 7 and 8 of the TRIPS Agreement “provide relevant context” to Article 20. (Ibid., para. 7.2399)

fn/1698 Panel Report, para. 7.2404.

fn/1699 Panel Report, para. 7.2406.

fn/1700 The degree of discretion reflected through the term “unjustifiably” in Article 20 is higher than it would have been, had the term reflecting the notion of “necessity” been used in this provision.

According to paragraph 6.657 above, the Appellate Body reached its conclusions “regardless of the legal status of the Doha Declaration.” This is somewhat disappointing, although better than a finding dismissing the legal status of the 2001 Declaration.

The panel reports made a clear statement about the legal status of the Doha Declaration, and the Appellate Body decided to resolve the case without taking a stance on the status of the Doha Declaration. This was also not the worst case scenario, which would have been to contradict paragraph 7.2410 of the panel reports – which Honduras sought in their appeal. Instead, the Appellate Body concluded that “the reliance on the Doha Declaration was not of decisive importance for the Panel’s reasoning since the Panel had reached its conclusions about the contextual relevance of Articles 7 and 8 of the TRIPS Agreement to the interpretation of Article 20 before it turned to the Doha Declaration.”

Despite the silence of the Appellate Body regarding the legal status of the Doha Declaration with respect to the TRIPS agreements, the reports upheld all of the findings by the panel in favor of Australia. Noticeably, in interpreting the ordinary meaning of the term “unjustifiably” the Appellate Body concluded that WTO members “enjoy a certain degree of discretion in imposing encumbrances on the use of trademarks under Article 20 of the TRIPS Agreement.” (WT/DS435/AB/R and WT/DS441/AB/R, paragraph 6.659) This and other findings in favor of plain packaging are, overall, a decisive victory for public health.

Finally, the decision does provide a robust interpretation of the importance of Part 1 of the TRIPS and Articles 7 and 8 in particular, and this will be important for future intellectual property disputes involving matters other than health, including those relating to social and economic welfare, and the public interest in sectors of vital importance to countries’ socio-economic and technological development.

AGREEMENT ON TRADE-RELATED ASPECTS OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS

Article 7, Objectives

The protection and enforcement of intellectual property rights should contribute to the promotion of technological innovation and to the transfer and dissemination of technology, to the mutual advantage of producers and users of technological knowledge and in a manner conducive to social and economic welfare, and to a balance of rights and obligations.

Article 8, Principles

1. Members may, in formulating or amending their laws and regulations, adopt measures necessary to protect public health and nutrition, and to promote the public interest in sectors of vital importance to their socio-economic and technological development, provided that such measures are consistent with the provisions of this Agreement.

2. Appropriate measures, provided that they are consistent with the provisions of this Agreement, may be needed to prevent the abuse of intellectual property rights by right holders or the resort to practices which unreasonably restrain trade or adversely affect the international transfer of technology.